Joan Wildman, Professor Emeritus of Jazz Studies at the Mead Witter School of Music, passed away April 8, 2020. She was 82 years old.

Born January 1, 1938, Joan grew up on a ranch near Spalding, Nebraska as an only child. She credited her friendship and mutual appreciation of blues and ragtime with the nearby Glaser family (the same Glaser brothers who went on to form Glaser Sound Studios in Nashville) as a major influence on her own career.

A major influence herself on generations of jazz musicians throughout Madison and beyond, Joan played an especially critical role in establishing the current jazz studies program at the school. Known to deftly explore the area between structure and improvisation, Joan was a professor of music at UW from 1978 through 2002 specializing in music theory, jazz improvisation, and jazz piano.

Double bassist Hans Sturm recalls Joan’s “uncompromising” approach to her music. Hans came to UW-Madison in the early ’80s to study with Professor Richard Davis, and eventually started playing in the Joan Wildman Trio.

“She was a big reason why I stayed in Madison for so many years,” Hans said. “Working with Joan really changed a lot of my concepts with music.”

While she was a classically trained pianist, Joan charted new territory and created her own sounds. She was an early adopter of the Yamaha DX 7, a digital synthesizer that allowed her to experiment with true crescendos and sustained attacks. Joan was also an early pioneer of crafting exceedingly long loops on her computer and emulator, often 80 to 90 bars long with 20 bars of silence and a groove the trio would play along with.

“She was fearless in her music,” Hans said. “We would rehearse for hours, and there might have been some intricate plan, but all that would disappear during the gig and the piece would take another shape. It was about where the music would take us. That’s kind of how Joan lived her life.”

Founder of the Madison Music Collective, a nonprofit jazz organization, Joan had a knack for bringing musicians together and promoting their work, a skill Hans said can’t easily be replicated.

Though she performed less later in life, Joan was an active performer both nationally and in the Madison area. She led her trio for over 25 years, producing recordings such as Orphan Folk Music (1987), Under the Silver Globe (1989), and Inside Out (1992).

One of her more recent releases was the 2015 album Conversations, a live recording with longtime friend and frequent collaborator Joe Fonda during a celebration of Madison Music Collective’s 30th anniversary at the Brink Lounge.

Madison writer Dean Robbins often covered Joan’s work and many of the trio’s performances over the years.

“Joan loved experimentation, but hers was the kind that drew listeners in rather than shutting them out,” Dean said. “No matter how far she strayed from conventional forms, she never lost sight of blue notes, swing rhythms, and other sensual pleasures associated with jazz. She even gave the synthesizer a human warmth, the notes melting under her touch. In this way, Joan’s sounds matched her spirit: big-hearted, soulful, searching. Like her hero Duke Ellington, she made idiomatic American music that perfectly balanced passion and intelligence.”

Joan was equally adept at creating computer-generated animations, web pages, and computer-generated drawings. Her extensive overview of jazz history and styles formed one of the first web pages in the country, a site that incorporated multi-media animations, sound and static visuals, and hyperlinked text.

Before coming to Wisconsin in 1977, Joan received her Doctor of Musical Arts degree from the University of Oregon and had previously taught at Central Michigan University and at the University of Maine, Fort Kent. She is the first and only member of her extended family to have achieved a doctoral-level degree.

“Joan gave so much to the School of Music,” Director Susan Cook said. “She was a path-breaking composer and performer in jazz, and with her colleagues and students, she was a dynamic force in the Madison jazz scene. Personally, she was a mentor to me when I joined the faculty in 1991, and in her retirement she continued to take an active interest in the school and lend her support.”

Like the rest of the world, faculty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Mead Witter School of Music are adjusting to new routines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Associate Professor of Horn Daniel Grabois talks about a few of the techniques he’s using to stay connected with students during this challenging time.

- Tell us more about the drill book you wrote. How did that come about?

As soon as we heard about the shutdown (that very night) and knew we would all be teaching remotely, it became very important to me to make sure my students were hitting all the basics every day in their practicing. Being a smart practicer is hard for ALL of us, no matter the level of education, and it is easy to lose motivation when we are apart from our colleagues.

For about four days, I played the whole routine through twice a day (it’s a one-hour routine), refining the drills, fleshing out details, nixing some drills and adding others, and so on. When I was satisfied, I started setting the book into Finale.

It was a complicated process. I set each drill into its own Finale file, and then I placed the Finale files into an Apple Pages document to lay out the book (I usually use Word for my documents, but Pages is much more friendly when it comes to mixing words and images). In the end, for every drill, I had to create a PDF in Finale, then open the PDF in Acrobat and crop it, then pop it into the Pages document and resize it. Any change I made in the drill after that involved resetting in Finale and going through the whole process again. The text surrounding the drills went through around 10 drafts (thanks to my wife, my brother, and my mom!).

On the eleventh day, I got it off to my publisher with a request that we make it cheap so as not to take advantage of the pandemic in order to make a buck. He agreed to publish it as a download for $10, and released it the next morning, day 12. I beat my goal by two days! We sold 16 copies on the first day, which was a single title record for the publishing company.

- What sort of new opportunities are you finding to be possible online?

Online is HARD for teaching. Because of insufficient bandwidth, it is really hard to hear students. Yes, you can hear them, but you can’t hear their actual sound, and you can’t hear details. In this online world of ours, we music faculty are recognizing that being in the room with a student beats every option.

That said, this has opened up new opportunities. For instance, I invited my old horn professor, who is now 88 years old, to talk to my students in studio class and to talk to the brass chamber groups I’m coaching.

I had a friend of mine who is an incredible electro-acoustic violinist talk to my electro-acoustic improv group, and another friend from that world will be doing the same thing in the future. Musician colleagues are willing to do this for each other because it is just a wonderful group of people who perform music for a living.

- Any additional advice for students during this time?

We all have more time than we normally do during the semester. That means we can practice more carefully, but we can also listen to more music, get in shape, eat right, and sleep enough. Let’s find the silver lining wherever we can.

Oh, the Games Lovers Play! Love, fidelity, partner swapping, and morality collide in Mozart’s topsy-turvy COSÌ FAN TUTTE

Contact: David Ronis, Karen K. Bishop Director of University Opera, ronis@wisc.edu, 608-263-1932

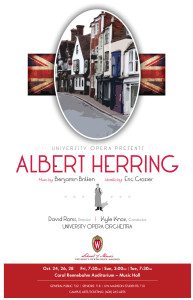

Following this fall’s sold-out run of Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, University Opera continues to explore the vicissitudes of love with Mozart’s beloved Così fan tutte. Blending rollicking humor with keen insight and barely concealed cynicism, Così features some of the most ravishing music Mozart ever wrote.

Three performances of this masterpiece will be presented at the Music Hall on the UW–Madison campus on February 28 at 7:30p.m., March 1 at 2:00p.m., and March 3 at 7:30p.m. The Mead Witter School of Music’s new Director of Orchestral Activities, Oriol Sans, will conduct the UW–Madison Symphony and Karen K. Bishop Director of Opera, David Ronis, will direct the production.

The story of Così is relatively straightforward. On a dare from Don Alfonso, Ferrando and Guglielmo don disguises to test the faithfulness of their fiancées by wooing each other’s betrothed. Much comedy ensues. The women – goaded by their maid, Despina, who is on the take from Alfonso – at first resist, but eventually give in and fall in love with the “wrong” men. In the end, all is revealed and ostensibly resolved.

But beneath the surface, things aren’t so simple. As the plot develops, the characters are drawn into murky psychological and emotional territory and troubling questions emerge. Is love really so fleeting? When the women fall for the “wrong” men, do the men’s affections also shift to their new partners? And what about Don Alfonso, the instigator of the whole affair? And Despina, the ladies’ maid, who is also complicit. What’s in it for them? When all is said and done, what kind of toll does this partner-swapping take on everyone involved? For all its hilarity, Così fan tutte ends up being a complex psychological study of human nature that addresses serious questions about love and attachment.

The UW-Madison production places Così in 1920, a time in which the early women’s rights movement was gaining momentum. Against this backdrop, this story of male manipulation takes on greater dimensionality and nuance. When Despina encourages the ladies to have affairs with the “strangers,” she embodies the kind of free spirit emblematic of the roaring 20s. Likewise, Don Alfonso, written as an eighteenth-century libertine, becomes a true bon vivant in this milieu – another example of the spirit of the times. What’s more, the choices that the four lovers face can easily be seen to mirror the shifting social landscape of the post-World War I era.

The cast features Rachel Love and Cayla Rosché alternating as Fiordiligi, and Chloe Agostino and Julia Urbank splitting the performances as Dorabella. Carly Ochoa, Anja Pustaver, and Kelsey Wang will all sing the role of Despina. On the men’s side, Benjamin Hopkins will sing Ferrando, Kevin Green will play Guglielmo, and James Harrington will be Don Alfonso.

The production will be designed by Joseph Varga with lighting by Zak Stowe. Sydney Krieger and Hyewon Park will be the costume designers; Lydia Berggruen, the props designer; Jan Ross, hair and wig designer, and the production stage manager will be Dylan Thoren. Others on the production staff include Benjamin Hopkins, operations manager for University Opera; Alice Combs, master electrician; assistant stage managers Grace Greene and Cecilia League; and Ashley Haggard and Kelsey Wang, costume assistants.

University Opera is a cultural service of the Mead Witter School of Music at the University of Wisconsin–Madison whose mission is to provide comprehensive operatic training and performance opportunities for our students and operatic programming to the community. For more information, please contact opera@music.wisc.edu. Or visit the School of Music’s website at music.wisc.edu.

Venue: Music Hall, 925 Bascom Hall

The Carol Rennebohm Auditorium is located in the Music Hall, at the foot of Bascom Hill on Park Street.

Tickets: $25 general public/$20 senior citizens/$10 UW–Madison students

Online:

Campus Arts Ticketing office at (608) 265-ARTS and online at http://www.arts.wisc.edu/ (click “box office”).

In-person:

Wisconsin Union Theater Box Office Monday-Friday, 11:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. and Saturdays, 12:00 – 5:00 p.m.

Vilas Hall Box Office, Monday-Friday, 11:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m., and after 5:30 p.m. on University Theater performance evenings.

Day-of:

Tickets may also be purchased at the door beginning one hour before the performance.

Parking: https://www.music.wisc.edu/about-us/parking/

More information: https://www.music.wisc.edu/event/university-opera-mozarts-cosi-fan-tutte/all/

Contact: Jay Rath

(608) 438-0127

Phyllis Bechtold Leckrone, 81, wife of longtime UW Marching Band director Mike Leckrone, passed away early this morning following a long illness. She was surrounded by family.

A native of North Manchester, Ind., she and her husband met in junior high school and became childhood sweethearts. They were married 62 years.

A dedicated educator in her own right, Phyllis Leckrone taught with the Middleton-Cross Plains school district for more than 25 years.

Mike Leckrone joined the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1969. Since then, Phyllis has served as “band mom” to thousands of marching band students. Though behind-the-scenes, her care, dedication and support touched generations of Badger Band members.

Mike and Phyllis Leckrone married in 1955. She is survived by five children, eight grandchildren and three great grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements will be announced soon. In lieu of flowers, the family asks that memorials be made to her favorite charity, St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital.

New opera sheds light on Artemisia Gentileschi, one of the Baroque’s most respected female painters

By Michael Muckian

Artemisia, the recently completed opera by the University of Wisconsin’s Laura Elise Schwendinger, has been scheduled for its world premiere performance January 7 in New York City as part of Trinity Church Wall Street’s 2016-2017 performance season.

A concert performance from the opera about 17th Century Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi by Schwendinger, professor of music composition at the UW’s Mead Witter School of Music, will be part of the ensemble’s Time’s Arrow Festival. Schwendinger’s composition will be one of four world premieres to be performed during the free concert series. Schwendinger has written large vocal works before, but this is her first opera.

“This is a magnificent group of musicians, and maestro Julian Wachner is a gifted composer and conductor who is always challenging himself,” Schwendinger said. “It is an honor to have my work presented by them.”

The annual festival, which features music spanning three centuries, will take place at St. Paul’s Chapel, located at 209 Broadway. The concert series will help celebrate the 250th anniversary of St. Paul’s, Manhattan’s oldest church whose doors first opened October 30, 1766.

The January performance of Artemisia, co-commissioned by New York’s Trinity Wall Street Novus and San Francisco’s Left Coast Chamber Ensemble, will feature mezzo-soprano Patricia Green as Artemisia, Marnie Breckenridge as Susanna, baritone Andrew Garland as Tassi and tenor Andrew Fuchs as Tomasso. The performance is free.

“The story of Artemisia hit me when I was an artist-in-residence in Rome (in 2009),” said Schwendinger, who herself paints. “I visited a lot of galleries and was struck by her works, including “Judith Slaying Holofernes.” There weren’t very many acclaimed women painters at the time.”

Schwendinger and librettist Ginger Strand, essayist and author of The Brothers Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in the House of Magic (Farrar, Straus & Giroux 2015), hope that Artemisia will change the historical perception of Gentileschi, who lived from 1593 to 1656.

Schwendinger, the first composer to win the American Academy in Berlin Prize, read a biography of the artist, who like many of her contemporaries worked in the style of Caravaggio. It was during discussions with Strand, a former college art history major who was aware of Artemisia and her work, that the idea of an opera based on her life began to gel.

“This is the kind of project that mixes my love of art with the story of an important women artist,” Schwendinger says. “It’s a nice connection.”

While Gentileschi holds the high honor of being the first female member of Florence’s prestigious Accademia di Arte del Disegno and was a respected artist in her time, history books remembered her more as a teenage victim of rape by her tutor, fellow artist Agostino Tassi.

Following the assault and the older Tassi’s ultimate failure to marry the 16-year-old girl as promised, Gentileschi’s father, the Tuscan painter Orazio Gentileschi, pressed charges against Tassi for taking his daughter’s virginity. The lawsuit, highly unusual for the time, resulted in long, protracted proceedings, during which Gentileschi was subject to gynecological exams and torture to verify her testimony.

The proceedings also revealed a plot by Tassi to murder his wife, adding to the sensationalism of the lawsuit. Tassi eventually was sentenced to one year in prison, but never served any time.

Gentileschi would go on to have a long and successful career, rare for a female painter in her time. But later generations would obscure her contributions to the Baroque period, and some of her work was even attributed to other artists.

In recent years, that perception has begun to shift back, with Gentileschi again credited as one of the period’s greatest painters. Schwendinger hopes her opera can spread Gentileschi’s story, further righting the wrong done to her by historians.

Born in Mexico City to a pair of U.S. foreign exchange students and raised in Berkeley, California, Schwendinger began making up melodies at age 4 and playing the flute at age 8.

When she applied to the San Francisco Conservatory of Music to study flute, her application included several compositions as well, which caught the eye of composer John Adams, best known for his operas Doctor Atomic and Nixon in China. He invited her to study composition with him, and she afterward went on to receive both her master’s degree and Ph.D. in music from the University of California-Berkeley, where she studied with her mentor and thesis advisor Andew Imbrie.

Her career has since seen her music played extensively both here and abroad, including at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, Wigmore Hall in London and the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, and has been toured as well as recorded by some of the leading musicians of our time, including the singer Dawn Upshaw. She has been a professor at UW-Madison for more than a decade.

The University recently awarded her a $60,000 Kellett Mid-Career Award, a grant sponsored by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and awarded to nine other faculty members for the 2016–17 academic year.

Schwendinger also received $16,500 as part of OPERA America’s $200,000 Discovery Grants for Female Composers, awarded to seven women and seven opera companies, which she will use in addition to the Kellett Award to mount upcoming productions of Artemisia. The entire opera will be fully produced by the award-winning Left Coast Chamber Ensemble in San Francisco in 2018.

“I hope that Artemisia resonates with those there and beyond, but that is not something a composer can predict,” Schwendinger said. “The composer creates the best art she can and hopes that it will mean something to the public and move the people who experience it.”

BRASS, BRASS AND MORE BRASS – With No. 3, UW-Madison cements a tradition as a Brass Hub of the Midwest

On September 30 and October 1, 2016, the newly renamed Mead Witter School of Music will welcome the internationally acclaimed Stockholm Chamber Brass to campus for a third annual Brass Fest. The quintet’s tour of upstate New York, Michigan and Wisconsin will be their first-ever appearances in the United States.

Brass Fest III will also mark the first time that high school students will play an active role, attending master classes and performing on stage in a final Festival Brass Concert. Area high schools planning to attend include Middleton, Madison East, Madison West, Edgewood, and Memorial.

A number of major instrument makers and music companies, many located in Wisconsin, will also be on hand to display their wares. The School will also offer commemorative fund-raising t-shirts; scroll to bottom to learn more.

The events will include a concert with Stockholm Chamber Brass on Friday, September, 30, at 8 PM, and a second concert on October 1, also at 8 PM, with the Stockholm Chamber Brass, the Wisconsin Brass Quintet, UW-Madison student performers and selected high school students. Both concerts will be held in Mills Hall in the Humanities Building.

Tickets: $20 for Friday’s concert ($5.00 non-music students); $15 for Saturday’s concert ($5.00 non-music students). Buy tickets here or at the door.

“We are expanding the festival because our mission is to perform and to teach,” says Daniel Grabois, assistant professor of horn and member of the Wisconsin Brass Quintet. “We are motivated by the Wisconsin Idea, and we are making every effort to bring what we do to the population of the state. There are many students in the state who play brass instruments, and we want to include them in our educational mission. We also want to build on the successes of the past two years – many people enthusiastically attended the festival, and we want to make it better, more exciting, and more inclusive.”

Stockholm Chamber Brass, formed in 1985, consists of some of Scandinavia’s leading brass musicians. Its five members are all prize winners at major international solo competitions, including the ARD-Wettbewerb, CIEM Geneve, Markneukrichen and Toulon. Their international breakthrough came in 1988 when Stockholm Chamber Brass won 1st Prize at “Ville de Narbonne,” the most prestigious international competition for brass quintets.

Stockholm Chamber Brass has performed at Bad Kissingen Sommer, the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, Niedesächsische Musiktage, International de Musique Sion Valais, the Prague Spring Music Festival, the Budapest International Music Festival, Festival Internacional de Santander, the Soundstream Festival in Toronto, the Belfast Festival at Queen’s, the Umeå International Chamber Music Festival and the Stockholm New Music Festival. The ensemble has also performed at various brass festivals, including the Lieksa Brass Week, the International Trombone Festival in Helsinki, the Melbourne International Festival of Brass, Epsival Limoge and the Blekinge International Brass Academy.

Stockholm Chamber Brass has received glowing reviews for its CDs. A reviewer at American Record Guide writes, “I cannot imagine that a better brass quintet has ever existed.”

The ensemble’s repertoire consists mostly of original compositions and their own arrangements of older and contemporary music. Their interest in new music has resulted in over thirty compositions written specifically for the ensemble. Stockholm Chamber Brass has worked with a long list of leading composers, including Anders Hillborg, Sven-David Sandström, Pär Mårtensson, Britta Byström, Henrik Strindberg Piers Hellawell and Eino Tamberg. The ensemble has also collaborated with leading brass soloists Håkan Hardenberger and Christian Lindberg.

The current members of the Stockholm Chamber Brass are Urban Agnas, trumpet; Tom Poulson, trumpet; Jonas Bylund, trombone; Annamia Larsson, horn; and Sami Al Fakir, tuba.

The Wisconsin Brass Quintet, formed in 1972, is one of three faculty chamber ensembles in-residence at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Mead Witter School of Music. Deeply committed to the spirit of the Wisconsin Idea, the group travels widely to offer its concerts and educational services to students and the public in all corners of the state.

The Wisconsin Brass Quintet includes John Aley, trumpet; Matthew Onstad, trumpet; Mark Hetzler, trombone; Tom Curry, tuba; and Daniel Grabois, horn.

New this year: Commemorative Limited Edition T-Shirts, featuring our new Brass Fest III logo on the front and “Mead Witter School of Music” on the back. Prices from $11 to $14; all proceeds will support the School of Music. Send an email to t-shirt sales if you’d like to buy one.

In homage to a beloved composer, the UW-Madison School of Music will present its third annual Schubertiade, an evening of songs, piano duets and chamber music by Franz Schubert, one day before the composer’s 219th birthday.

The concert will take place on Saturday evening, January 30, 2016 at 8 p.m. in Mills Concert Hall. The concert is hosted by pianist Martha Fischer, who is professor of collaborative piano and piano at the School of Music, and her pianist husband Bill Lutes, emeritus artist-in-residence. Alumna soprano Jamie-Rose Guarrine, who has sung with many major opera companies including Wolftrap in Washington, D.C., the Santa Fe Opera, the Minnesota Opera, as well as Milwaukee’s Florentine Opera and Madison Opera, will be a guest soloist. Guarrine now teaches at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Martha Fischer & Bill Lutes

Schubert was born on January 31, 1797, in Himmelpfortgrund, near Vienna in Austria, and died at age 31, yet in that short span managed to write some 600 works for the voice, seven symphonies, operas, chamber music, and much more. He influenced many composers, including Mendelssohn, Liszt, Brahms, and Schumann, and is now considered one of the most important composers of the late Classical and early Romantic eras.

Fischer’s and Lutes’s association with Schubert dates from their time as graduate students at the New England Conservatory of Music, where they discovered the composer and each other simultaneously. They married in 1984.

Schubertiades, which were popular during Schubert’s lifetime, were homey Viennese “house concerts” featuring the composer, fellow musicians and friends that offered music performances, dancing and carousing, often until dawn. At the School of Music, performers and patrons will be on stage together, seated in chairs and on sofas, to attempt to mimic the “house concert” style. For the first time, a public reception will be held afterwards.

The program will include a major work for piano duet, the Allegro in A minor, known as “Lebensstürme” or Life’s Storms, performed by Fischer and Lutes. Guarrine will sing one of Schubert’s final works, the delightful “Shepherd on the Rock,” along with Fischer and clarinet faculty Wesley Warnhoff.

Additional guests will include UW-Madison voice faculty Mimmi Fulmer and Paul Rowe; current University Opera director David Ronis; alumni singers Daniel O’Dea and Benjamin Schultz; current DMA candidate Sara Guttenberg; soprano Marie McManama; UW-Madison horn faculty Daniel Grabois; UW-Madison faculty violinist Soh-hyun Park Altino; UW-Madison faculty violist Sally Chisholm; adjunct professor of clarinet Wesley Warnhoff; alumnus cellist Ben Ferris; and Parry Karp, faculty cellist.

“The overarching idea for this year’s Schubertiade is music inspired by the motions and movements of the natural world, especially water, wind, and woodlands, forests and trees,” says Lutes. “The poems that Schubert chose for his lieder often feature vivid and evocative imagery from nature, while exploring our human emotional and spiritual responses to the natural world. As Schubert is moved by the natural world, we listeners are moved in turn by the sublime ‘nature music’ of his songs and instrumental works.”

Accordingly, the concert will offer one of Schubert’s best loved “water” songs, “Die Forelle” (The Trout) as well as the Theme and Variations movement derived from this song from the famous “Trout” Quintet for piano and strings.

This concert and future Schubertiades are being graciously underwritten by Ann Boyer.

Tickets are $15.00 for adults. Students of all ages are free.

Tickets are available through the Union Theater Box Office. Patrons may buy online ($4 fee) or save the fee and buy in person at Memorial Union or in Mills lobby day of show.

Please note: We recommend that patrons arrive early, both to secure a parking spot and to buy a ticket. Parking will be tight due to UW hockey, but parking passes may be ordered in advance to guarantee a space.

Options include H.C. White Garage (Lot 6); Fluno Center (Lot 83); University Avenue Ramp (Lot 20). VISA is accepted.

Complete this online request form or call the Special Events Office at (608) 262-8683. Please allow two weeks for processing. In the box for “special instructions,” please indicate “Schubertiade.”

In early November, the UW-Madison School of Music will welcome back five graduates of the composition studio who have developed creative, multi-dimensional careers in a range of fields: acoustic and electronic composition, musicology, theory, audio production, conducting, education, concert management and administration, performance, and other fields as well. The two-day event on Nov. 5 & 6 will feature concerts of chamber music and Wind Ensemble music, symposia on marketing, publicity, and career development, and ample opportunities for conversation.

The composers include Jeffrey Stadelman (BM, 1983; MM, 1985), now associate professor of music composition at the University at Buffalo; Paula Matthusen (BM, 2001), assistant professor of music at Wesleyan University; William Rhoads (BM, 1996), vice president of marketing & communications for Orchestra of St. Luke’s in New York City; Andrew Rindfleisch (BM, 1987), professor of composition at Cleveland State University; and Kevin Ernste (BM, 1997), professor of composition at Cornell University.

Music will be performed by the Wisconsin Brass Quintet, the Wingra Woodwind Quintet, the UW Wind Ensemble, and other faculty and students. The works being performed by both faculty and students range from standard instrumentations (woodwind and brass quintets) to unusual combinations (piano, percussion, clarinet, and oboe) to solo works performed by some of our most accomplished students.

Thursday, Nov. 5, 7:30 PM, Mills Hall, free concert. Click for program.

Friday, Nov. 6, 7:30 PM, Mills Hall, free concert. Click for program.

Additional sessions, to be held on Friday, Nov. 6 at the Student Activities Center, University Square:

11:30 – 12:10 Marketing for Musicians

Today, savvy understanding of marketing and pr is a necessity for performers and composers. Learn the basics of building an effective communications strategy to promote and publicize your event, your career, or your new work.

12:15 – 12:55 Publishing for Composers

With power shifting from large publishing houses to individual composers, it’s an exciting time to be a creative artist. Get an overview of the recent history and changes in music publishing and important guidelines on the myriad channels that exist which allow you benefit from the use of your music.

1 PM: Meet Bill Rhoads at CoffeeBytes.

All five composers grew up in Wisconsin or Minnesota, and they provide a variety of career models, in both industry and academia, in both live and electronic music, for our student composers and performers. This may be the first time that a university music school has brought together the alumni of an academic composition program, from a period of several decades, for concerts of their music, workshops with current students, and public informational events.

Here are composer biographies along with comments about their works.

Composer Andrew Rindfleisch has enjoyed a career in music that has also included professional activity as a conductor, pianist, vocalist, improviser, record producer, radio show host, educator, and concert organizer. As a composer, he has produced dozens of works for the concert hall, including solo, chamber, vocal, orchestral, brass, and wind music, as well as an unusually large catalog of choral music. His committed interest in other forms of music-making have also led him to the composition and performance of jazz and related forms of improvisation. “Their brass quintet, ‘In the Zone,’ is a pun on the Italian word ‘canzone,’ a style of piece often written for brass ensembles (the works of Gabrieli are great examples),” says Daniel Grabois, professor of horn. “If an old canzone were fractured and reassembled using a 21st century sensibility, the result would sound like this piece. At times it throbs with the wild abandon of a medieval band, and at other times grooves with the rhythmic snap and clarity of a group of Renaissance troubadours.” (Note: The Wisconsin Brass Quintet will perform “In the Zone” on the Thursday concert.) Listen to Rindfleisch’s music on SoundCloud.

Andrew Rindfleisch

Mr. Rindfleisch is the recipient of the Rome Prize, a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship, the Aaron Copland Award, and the Koussevitzky Foundation Fellowship from the Library of Congress. Over forty other prizes and awards have followed honoring his music. He has participated in dozens of renowned music festivals and has received residency fellowships from the Bogliasco Foundation (Italy), the Czech-American Institute in Prague, the Charles Ives Center for American Music, the June in Buffalo Contemporary Music Festival, the MacDowell Colony, and the Pierre Boulez Conductor’s Workshop at Carnegie Hall. He holds degrees from the University of Wisconsin at Madison (Bachelor of Music), the New England Conservatory of Music (Master of Music), and Harvard University (PhD).

As a conductor and producer, Mr. Rindfleisch’s commitment to contemporary music culture has brought into performance and recording over 500 works by living composers over the past 20 years. He has founded several contemporary music ensembles and currently heads the Cleveland Contemporary Players Artist in Residency Series at Cleveland State University, and the Vertigo Ensemble at the Utah Arts Festival in Salt Lake City. He has made guest conducting appearances throughout the United States and abroad with many diverse musical organizations; from opera and musical theatre, to orchestral, jazz, improvisational, and contemporary avant-garde ensembles.

Paula Matthusen writes both electroacoustic and acoustic music and realizes sound installations. In addition to writing for a variety of different ensembles, she also collaborates with choreographers and theater companies. She has written for diverse instrumentations, such as “run-on sentence of the pavement” for piano, ping-pong balls, and electronics, which Alex Ross of The New Yorker noted as being “entrancing”. Her work often considers discrepancies in musical space—real, imagined, and remembered. “A pleasant surprise in the Sunday morning program [for the Tanglewood Festival of Contemporary Music] was Paula Matthusen’s piece “of memory and minutiae” (2006), a plaintive, haunting setting of a Norwegian prayer that fragments further with each repetition. Olenka Slywynska gave the soprano line a chantlike quality while cello counterpoint and electronic timbres wove a graceful atmospheric cocoon around it.” Allan Kozinn, New York Times, 2009. Listen to Matthusen’s music on SoundCloud.

Paula Matthusen

Her music has been performed by Dither, Mantra Percussion, the Bang On A Can All-Stars, the Scharoun Ensemble, Mantra Percussion, Dither Electric Guitar Quartet, Alarm Will Sound, International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), orchest de ereprijs, The Glass Farm Ensemble, the Estonian National Ballet, James Moore, Kathryn Woodard, Todd Reynolds, Kathleen Supové, Margaret Lancaster and Jody Redhage. Her work has been performed at numerous venues and festivals in America and Europe, including the Tanglewood Festival of Contemporary Music, the MusicNOW Series of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Ecstatic Music Festival, Other Minds, the MATA Festival, Merkin Concert Hall, the Aspen Music Festival, Bang on a Can Summer Institute of Music at MassMoCA, the Gaudeamus New Music Week, SEAMUS, International Computer Music Conference and Dither’s Invisible Dog Extravaganza. She performs live-electronics frequently, often with Object Collection, and through the theater company Kinderdeutsch Projekts.

Awards include the Walter Hinrichsen Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a Fulbright Grant, two ASCAP Morton Gould Young Composers’ Awards, First Prize in the Young Composers’ Meeting Composition Competition, the MacCracken and Langley Ryan Fellowship, the “New Genre Prize” from the IAWM Search for New Music, and recently the 2014 Elliott Carter Rome Prize.

Matthusen has also held residencies at The MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, create@iEar at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, STEIM, and the Atlantic Center for the Arts. Matthusen completed her Ph.D. at New York University – GSAS. She was Director of Music Technology at Florida International University for four years, where she founded the FLEA Laptop Ensemble. Matthusen is currently Assistant Professor of Music at Wesleyan University, where she teaches experimental music, composition, and music technology.

Currently Vice President of Marketing & Communications for the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Bill Rhoads was previously President and Managing Director of Bill Rhoads & Associates, which was promotion agent for several publishing houses, including CF Peters, EC Schirmer, Subito Music and MMB Publishing; and represented the interests of Frank Zappa, John Zorn, Ornette Coleman, Ethel, counter)induction, Fred Ho, and two Pulitzer Prize-winning composers, along with a host of other prominent artists and firms in the music industry. Prior to opening his own firm, Mr. Rhoads was Director of the Concert Music Division for Carl Fischer, LLC in New York.

Bill Rhoads

He has been active as board member of the Phoenix Concerts, the Lotte Lehmann Foundation, Wisconsin Alliance for Composers, and co-director of Composers Concordance and E.A.R. (Elastic Arts Room) in New York City. In addition, Mr. Rhoads served the music industry as Communications Advisor for ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble), Board Member for CRI (Composers Recordings, Inc.), and the MPA (Music Publishers Association), as Honorary Advisory Board Member for The Women’s Philharmonic, and as panel member, speaker and judge on numerous committees for organizations serving the needs of composers, educators, and performers, including ASCAP, MENC, and the League of American Orchestras.

His work was influenced by his early experiences as guitarist in several rock bands, his training as an audio engineer and producer, background in philosophy and aesthetics, immersion into the experimental music scene of NYC, and composition studies with Stephen Dembski, Joel Naumann, Joseph Koykkar, John Corigliano, George Rochberg and John Harbison. It has been performed and recorded by ensembles throughout the U.S., including Sequitur and Composers Concordance in New York City, May in Miami Festival, Present Music in Milwaukee; and Bach, Dancing, and Dynamite and Oakwood Chamber Players in Madison. “Written idiomatically, even brilliantly, for the instruments at hand, Scherzophrenia springs from the “and now for something completely different” school of composition. Like John Zorn, its best-known practitioner, Rhoads quick-cuts snippets of familiar styles: cartoon illustrative music, lofty trumpet calls, Brahmsian piano trios, cheesy waltzes, clarinet horselaughs, rim shots. Rhoads wrinkle if to bring back his materials in different contexts – to remix them, as it were.” Tom Strini, music critic, The Milwaukee Journal, 1994. Listen to “Slam,” recorded in 2004.

With deep roots in American modernism, composer Jeff Stadelman has developed over the past 30 years a complex, lyrical musical language that suggests no obvious counterpart. Five CDs containing his compositions have appeared since 2007, including the solo monographic CD, “Pity Paid” (Centaur Records). Los Angeles Times critic Josef Woodard called the music “painterly . . . , deftly dispersed in time and glazed with a dry wit” while Jay Batzner, of Sequenza 21, describes it as a “powerful, caged beast … barely contained by its enclosure.” Listen to Stadelman’s music on SoundCloud.

Jeffrey Stadelman

Stadelman sees his music as “obsessed with <i>reference<i>, drawing deep sustenance from the classical works of past and present that most richly exploit possibilities for building associative structures of great beauty.”

Stadelman has received commissions and invitations for compositions from, among others, the Fromm Foundation and Boston Musica Viva, Nuove Sincronie, Concert Artists Guild, Trio Italiano Contemporaneo, Phantom Arts, Bernhard Wambach, Elizabeth McNutt, Jon Nelson and UW-Madison. Grants and awards include those from Meet the Composer, Harvard University, Friends and Enemies of New Music, and the Darmstadt Summer Courses.

Originally from Wisconsin, Stadelman serves as associate professor of music composition at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, as well as Department Chair. He studied composition as an undergraduate with Stephen Dembski at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and then with Donald Martino and others for his Ph.D. at Harvard University. His most recently recorded project is a large orchestral work entitled “Messenger,” which appeared in January 2013 on the Navona label. Stadelman writes, “My music tends to be up-tempo and syncopated, with emphasis on independent instrumental lines interacting energetically. People have pointed out that there often seems to be an ironic glaze over the proceedings, and in any case I favor what classical music calls “scherzoso” attitude — playful, even joking. However when my music gets serious, it’s _very_serious indeed. I am always interested in conjuring referential clouds of various sorts, where any particular musical

utterance is heard to ring of, or rhyme with, several others from other sections of the same piece. This music is generally in dialogue with one or more models from the past, and melody always comes first. Very recent works have focused on creating linked canons (rounds) between the instruments, with the actual chords looking backwards historically, but chordal progressions looking in some other direction.”

Kevin Ernste is a composer, performer, and teacher of composition and electronic music at Cornell University where he is Director of the Cornell Electroacoustic Music Center. He was the Acting Director and lecturer at the Eastman Computer Music Center and Co-director of the ImageMovementSound festival.

Kevin Ernste

His recent music includes Palimpsest for the JACK Quartet–the result of a 2011 Fromm Foundation Commission, presented recently at the Sweet Thunder Festival in San Francisco and the International Computer Music Conference in Athens Greece, Nisi [nee-see] (“Island” in Greek) for hornist Adam Unsworth released on Equilibrium Records “Snapshots” (CD111), Adwords/Edward, dedicated to NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden and composed for Google Glass, Numina for Brooklyn-based Janus Trio (flute, viola, harp) presented recently at the Spark Festival in MN, Seiend for brass quintet premiered by Ensemble Paris Lodron (Salzburg, Austria, Roses Don’t Need Perfume for guitarist Kenneth Meyer (gtr. and electronic sounds, 2009) recently presented by Dr. Meyer on his 2010 Hungary/Romania tour, a piece for saxophone and electronics called To Be Neither Proud Nor Ashamed (recently released on Innova Records), and Birches for viola with electronic sounds for John Graham performed on Mr. Graham’s recent China tour (Beijing, Wuhan, Xiamen, Hong Kong) as well as at the Aspen Summer Music Festival. Mr, Graham presented Birches again in August 2011 at the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC) in Huddersfield, UK and again in 2012 at CCRMA for the Linux Audio Conference. Listen to Ernst’s music on SoundCloud.

This two-day event is sponsored by the UW-Madison Anonymous Fund and the Mandel Foundation.

From October 9 to 11, the UW-Madison School of Music will present its second brass music festival, following a spirited event last year that was enthusiastically received by students and the community.

This year, “Brass Fest II” has added a vocalist to the mix: a Norwegian singer who mixes jazz tunes with pop and folk music from the Middle East, Bulgaria, Spain and India. The three-day festival will also features two brass quintets and a solo trumpeter.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”1″ gal_title=”Brass”]

The festivals showcase the energetic, eclectic world of brass music, says festival organizer John Aley, professor of trumpet at UW-Madison and principal trumpeter of the Madison Symphony Orchestra. “We benefited from creative energy last year that continues to impact positively in the School of Music,” says Aley. “The performances will showcase some amazing talent and innovation including the surprising and delightful synergy of brass plus voice.”

On the docket this year:

Friday, October 9: Axiom Brass Quintet, 8 PM, Mills Hall. This lively Chicago quintet features repertoire ranging from jazz and Latin music to string quartet transcriptions, as well as original compositions for brass quintet. Friday’s concert will offer an Elizabethan suite, “The Art of the Fugue” by J.S. Bach, and brass quintet works by Victor Ewald, David Sampson, and Patrice Caratini.

Axiom Brass is an Ensemble-in-Residence at the Boston University Tanglewood Institute and at Chicago’s Rush Hour Concerts. They are winners of the Chamber Music Yellow Springs Competition (2012), the Preis der Europa-Stadt Passau in Germany (2012), the 2008 International Chamber Brass Competition and prize-winners of the 2010 Fischoff Chamber Music Competition, the Plowman Chamber Music Competition, and the Jeju City International Brass Quintet Competition in South Korea. Axiom Brass is comprised of Dorival Puccini, Jr., trumpet; Jacob DiEdwardo, horn; Kevin Harrison, tuba; Serdar Cizmeci, trombone; and Kris Hammond, trumpet.

Saturday, October 10: Festival Brass Choir with the Axiom Brass Quintet, the Wisconsin Brass Quintet, trumpeter Adam Rapa, vocalist Elisabeth Vik, and students/faculty of the School of Music. 8 PM, Mills Hall. Conducted by Scott Teeple, professor of music and wind ensemble conductor. The concert will include works by Astor Piazzolla, James M. Stephenson, Anthony DiLorenzo, Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and a Bulgarian vocal work sung by Ms. Vik.

The Norwegian-born vocalist Elisabeth Vik was classically trained by Norwegian opera singer Rolf Nykmark, then moved on to study commercial music and music business at the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts in England. She received a bachelors degree in pop-music performance, then moved to New York City. She has traveled the world gathering and learning techniques and musical expressions, giving her sound and stylings hints of Indian, Arabic, Spanish, Bulgarian as well as Norwegian flavors, superimposed upon a classical technique and an affinity for jazz.

American Adam Rapa is a dynamic performer, composer, producer and educator known for the excitement, energy and enthusiasm he brings to stages and classrooms around the world. Rapa has been featured as a special guest artist and clinician at trumpet conferences around the globe including the International Trumpet Guild conference, the National Trumpet Competition, and festivals in dozens of countries around the world. Adam performed and/or recorded with Grammy Award winners Nicholas Payton and Roy Hargrove, Christian McBride, Doc Severinsen, Soulive, Wycliffe Gordon, Eric Reed, Jason Moran, Robert Glasper, Cyrus Chestnut, Jorge Pardo, Mnozil Brass, Belgian Brass, Alice in Chains, Academy Award winning film composer A.R. Rahman, and many others. Now living and freelancing in Copenhagen, Rapa plays lead trumpet in the Danish Radio Big Band and also performs with members of the Afro-Cuban All-Stars.

The Wisconsin Brass Quintet, formed in 1972, is a faculty ensemble in residence at the UW-Madison. In addition to performing with the WBQ, the players have also been members of the American Brass Quintet, Empire Brass Quintet and Meridian Arts Ensemble. Current members include Tom Curry, tuba; Mark Hetzler, trombone; Daniel Grabois, horn; John Aley, trumpet; and Matthew Onstad, trumpet.

Sunday, October 11: Duo recital with trumpet soloist Adam Rapa, vocalist Elisabeth Vik, and musicians from the School of Music. 7:30 PM, Mills Hall. Based in Denmark, the duo offers a creative blend of classical and jazz, melding traditional and modern repertoire with a Latin sizzle. Works will include the Carmen Suite by George Bizet, Så Skimrande Var Aldrig Havet by Evert Taube, arranged by Rapa & Vik, Oblivion by Astor Piazzolla arranged by Rapa, and Anitras Dance by Edvard Grieg, arranged by Vik & Rapa.

Tickets for the Friday and Saturday concerts are $15 for adults, free for students and children. Sunday’s concert is free to all.

Buy tickets to both concerts and save!

In September, the UW-Madison School of Music will welcome violinist Soh-Hyun Park-Altino to its roster of full-time faculty. Prof. Altino hails most recently from Memphis, where she served on the faculty for 14 years.

Read Prof. Altino’s biography here.

Save the Date: Prof. Altino will make her concert debut in Madison with pianist Martha Fischer on November 13, 8 PM in Mills Hall. Tickets $12, and available at the Memorial Union Box Office or day of show at Mills Hall. Student admission is free.

Soh-Hyun Park Altino. Photograph by Caroline Bittencourt.

What motivated you to seek the position here at UW?

I first heard about the UW-Madison School of Music and its fantastic string faculty when I was attending the Cleveland Institute of Music as a graduate student. Later while I taught at the University of Memphis, I often encouraged my students to consider UW-Madison for further schooling because of the reputation of the faculty. So I was excited to find out about the violin position last fall, and I am honored to be joining such an excellent community of musicians and scholars here at UW-Madison.

What gives you the greatest pleasure as a teacher of young students?

My greatest joy as a teacher is the up-close witness of the journey that each student takes throughout the course of his or her study. As we discuss and explore countless ways to communicate a story through the sound of a violin, sooner or later students face challenges that would push them beyond the familiar and the manageable. I love seeing my students grow to the point of taking steps of courage and giving generously from their hearts in spite of the difficulties presented in their pieces. The confidence gained by these experiences remains with them for the long haul.

Do you have special qualities, strengths, skills that you’ve honed over the years?

I believe, in order to be able to truly help my students grow as individual violinists and artists, I need to first get to know and understand how each one hears music. Different people will hear different things in the same performance. My role is to help them become aware of other things that are going on in the music and to assist them in acquiring necessary tools to express these ideas. My students often tell me that I am very patient during lessons; that always sounds funny to me because I think of myself as a impatient person in general. Working out long-standing and unhelpful physical habits in my students’ playing energizes me as I hear and see the freedom in their music just around the corner.

Do you enjoy performing any particular musical styles/time periods?

I enjoy learning and performing all good music, from the Baroque to the contemporary. While I love chamber music of all kinds, my favorite genre is works for violin and piano. It feels like an intimate conversation between two close friends that are inherently very different from each other.

Where have some of your students gone after study with you?

It’s extremely important for me to guide each of my students toward a career path that would make use of their individual gifts and strengths. Many of my students have gone on to study at major conservatories and universities and after schooling, they secured professional positions in various places. Some are teaching at colleges, in school string programs, and in Suzuki schools while some are performing in professional orchestras. And some others have found their calling in musicology and arts administration. I truly believe that, for us musicians, our satisfaction in what we do depends largely on the sense of continual growth.

You will bring your husband, a cellist. Have you collaborated?

My husband, Leo, and I met playing and teaching together at a festival, and we have performed concertos, duos, piano trios and beyond ever since. We love to play with and for each other and value each other’s honest commentaries; over the years we have become each other’s teacher. We are just beginning to get to know the area and are very excited about our new adventure in the musically dynamic city of Madison.

Had you been to Madison before?

My first time in Madison was for the interview and audition for this position in April, and I didn’t know a lot about the city, but since accepting the position, everyone around me has given me nothing but enthusiastic reports about Madison. My family and I moved to Madison in late July, and I have to agree with my friends’ opinions about the city.

Do you have an inkling of your concert program?

I am so looking forward to working with Martha Fischer and presenting a recital with her in November. The program includes the C major solo sonata by Bach, the second sonata by Brahms, and Charles Ives’s sonata no. 2.

The 2015 fall semester at the School of Music will be marked by the addition of a new tenure-track professor of violin, Soh-Hyun Park Altino, and adjunct professor of clarinet, Wesley Warnhoff.

Park Altino replaces Felicia Moye, a tenured violin professor who decamped to McGill University in the summer of 2014 and was replaced for 2014-2015 by Leslie Shank. Warnhoff replaces Linda Bartley, a tenured professor of clarinet who has retired. Below are their official biographies.

Violinist Soh-Hyun Park Altino is highly regarded as a gifted teacher and a versatile performer of solo and chamber music. Her concert engagements have taken her to Brazil, Colombia, Germany, Korea, Venezuela, and throughout the United States. Praised for her “poise and precision,” she has appeared as soloist with the Memphis Symphony, Jackson Symphony, Peabody Concert Orchestra, Masterworks Festival Orchestra, Sinfonica de Campinas in Campos do Jordão, Festival Virtuosi Orquestra in Recife, and Suwon Philharmonic in Seoul among others.

Soh-Hyun Park Altino. Photograph by Caroline Bittencourt.

She has collaborated with renowned artists such as Monique Duphil, Oleh Krysa, Suren Bagratuni, Daniel Shapiro, and Jasper de Waal in festivals such as Duxbury Music Festival, Masterworks Festival, the Academy y Festival Nuevo Mundo in Venezuela, and in the Memphis Chamber Music Society concert series.

Prior to her joining the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Music in 2015, Soh-Hyun served on the faculty at the University of Memphis for fourteen years. During her tenure at Memphis, she frequently performed with pianist Victor Asunción and cellist Leonardo Altino in the Dúnamis Trio, and as a member of the resident ensemble, Ceruti Quartet, she presented recitals and educational programs throughout the U.S. as well as at the National Assembly in Seoul, Korea and Teatro Santa Isabel in Recife, Brazil. The quartet’s recording of the Debussy Quartet released in 2013 was hailed by Gramophone for its “physically emotional power.” As an enthusiastic supporter of new music, she has enjoyed working closely with composers such as Steven Mackey, Margaret Brouwer, James Mobberley, and Kamran Ince, and in 2014 she premiered a commissioned work, En Voyage for violin and cello, by Paul Desenne.

As a dedicated teacher, Soh-Hyun directed the String Intensive Study Program at Masterworks Festival for eleven summers, taught through projects such as Fabrica de Musica and eMasterclass in Brazil and Festival y Escuela Internacional de Musica in Colombia, and presented violin master classes at universities nationally and internationally. Her experiences and insights gained from overuse injuries as a student have served as one of the major factors that inspire her passion and inquisitiveness for teaching, and she has become an advocate of continuing education for performers and teachers. To this end, she has regularly presented professional development sessions and held forums and clinics for violin teachers and their younger students. While her former students are national competition prizewinners and members of professional orchestras, a great many of them are devoted teachers at colleges and string programs across the country.

A native of Korea, Soh-Hyun grew up in a musical family and studied with Young-Mi Cho. At age sixteen, she came to the U.S. and studied with Violaine Melançon at the Peabody Institute where she was also given intensive training in chamber music and music theory, and she was a participant at Yellow Barn, Kneisel Hall, Tanglewood, Aspen, and Sarasota Music Festival. Her major chamber music coaches include Anne Epperson and the members of the Peabody Trio and the Juilliard, Concord, Cavani, and Cleveland Quartets. Soh-Hyun received her bachelor’s, master’s and the doctor of musical arts degrees in violin performance from the Cleveland Institute of Music, where she was a student and teaching assistant to Donald Weilerstein.

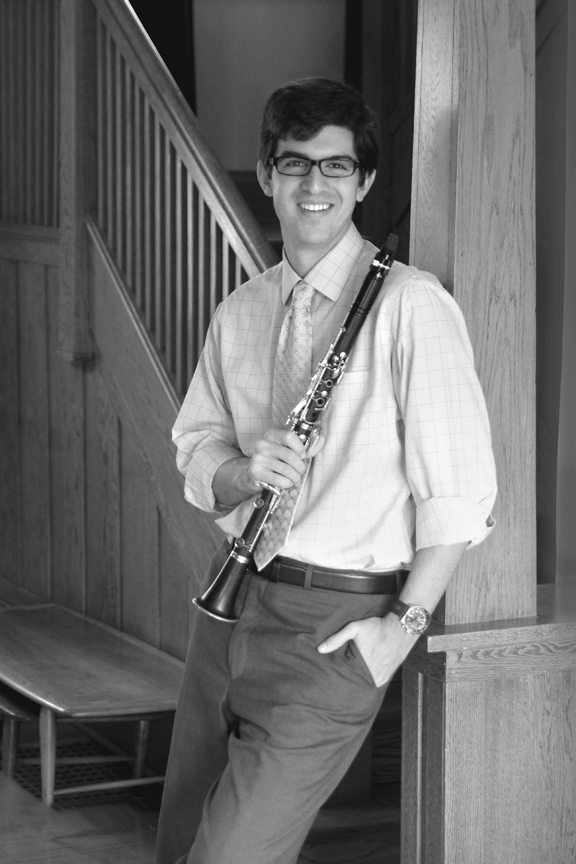

Wesley Warnhoff

American clarinetist Wesley Warnhoff’s thoughtful and intense performance style has gained him international acclaim as a soloist, orchestral, and chamber musician. Dr. Warnhoff’s research into contemporary techniques has helped him to develop a unique pedagogical approach that provides a new perspective on creating the ideal embouchure and sound concept, and it is this dedication to the art of teaching that makes Dr. Warnhoff a sought after clinician throughout the United States.

As a champion of new music he has given many premiere performances including the world-premiere of Murray Gross’ Rhapsody for Clarinet, I Surrender. Along with performing new music, Dr. Warnhoff has also added to the performing repertoire, most notably with his transcription for clarinet, voice, and piano of “La Vita e Inferno” from Verdi’s La Forza del Destino.

Dr. Warnhoff is currently on the music faculty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where he leads the clarinet studio and performs with the renowned Wingra Woodwind Quintet. He is a founding member of the VCP International Trio, a violin, clarinet, piano trio that advocates new music performance, and he is also the principal clarinet of the Battle Creek Symphony Orchestra in Michigan, a post he has held for 5 years.

Dr. Warnhoff holds degrees from Michigan State University and Missouri State University. His primary teachers are Dr. Elsa Ludewig-Verdehr, Dr. Allison Storochuk, and Dr. Jack Scheurer.

At the School of Music’s “Horn Choir” concert at the Chazen Museum of Art last month, one could easily discern John Wunderlin from the swarm of horn players on the stage.

He was the only one with gray hair.

UW’s Horn Choir at a recent concert, at the Chazen Museum. Wunderlin is second from right. Daniel Grabois, conductor.

That’s because he’s 50 years old. It’s safe to say that most of the other performers were about the ages of his two kids, 23 and 19. And yes, he is a student.

After a full life as a business owner, husband and dad, Wunderlin returned to school this fall for a master’s degree in horn. He first studied the instrument in college (way back when) and played as much as possible over the years. But after he met Dan Grabois, assistant professor of horn at UW-Madison, he finally took the leap and applied for the program at UW. He says he likes Dan’s teaching style. “[Dan] offers a lot of concrete suggestions, as opposed to someone who says, ‘it’s my way or the highway,’ ” Wunderlin says.

We asked John to tell us a bit about his unusual career path.

What made you want to come back to school for a masters degree?

“It was always a long-term goal of mine to come back to school. My undergraduate degree was computer science with a music minor from UW-Platteville. As an undergrad, I made a conscious decision to earn a degree that would allow me to make a good living, but music was always my passion. With a long career in computers and both my children grown, it seemed like the right time to focus on music.

John Wunderlin. Photo by Katherine Esposito.

What was your previous career, and how did the horn fit in?

“I spent 27 years working as a computer programmer. First for several large corporations, then as an independent contractor, and for the last 14 years I ran my own software business with my wife Nancy. After college, I didn’t stop playing the horn. I was always looking for gigs, but did try to balance my rehearsal schedule with my home life- we have two children. In 1999, I came across a summer camp called the Kendall Betts Horn Camp in New Hampshire. This is a camp for horn players of all ages from high school to seniors with world-class horn faculty. It was a week-long opportunity to immerse in music that I have taken advantage of nearly every year since. I credit KBHC with improving my playing significantly to the point that I won my first regional orchestra audition with the Beloit-Janesville Symphony (now called the Rock River Philharmonic). I’ve been a member there for the last six seasons.

Why UW-Madison?

“I’ve played a lot of gigs in the Madison area and my wife and I both love the town. We lived in Mineral Point for the last 21 years. This was a good opportunity (and a good excuse) to move to Madison. I considered a few other universities, but after working with Dan Grabois and considering my options, it was really an easy choice.

What is it like being having student colleagues in their 20s and even late teens?

“The other students in the horn studio have been absolutely terrific! From day one they treated me like just another student. I’m amazed at the sense of camaraderie and lack of competitiveness within our studio. I feel like everyone’s goal is to support and help each other become the best musicians we can all be.

Have you had any trouble adapting or fitting in?

“Very little. I’m not the only non-traditional student in the music department. There are a range of ages, though I’m probably a bit above the median.

What do you hope to gain from the degree and the experience here at UW?

“My primary short-term goal is full musical immersion for the next two years. Beyond that, I’m interested in winning a larger orchestra job and/or teaching at a college or university.

Any advice for people thinking of going back to school for a performance degree?

“The field of music performance is an extremely competitive area with many, many more musicians than available jobs. My first recommendation would be to save a lot of money before starting to give yourself some time to find a job and consider other options if things don’t work out. My second recommendation is to jump in with both feet. It’s a lot of hard work, but also very rewarding. When I’m performing with a great group of musicians and in ‘the zone,’ there’s nothing else I’d rather be doing. Personal problems, politics, bad thoughts all melt away and are replaced with a musical connection with my talented colleagues that transcends words.”

When Teri Dobbs was twelve years old, growing up in the tiny farming town of Platte, South Dakota, her mother took her aside and broached a topic that would forever change the young girl’s life.

“My mom started educating me about the Holocaust, and gave me a book,” says Dobbs, an associate professor of music and chair of the music education program at UW-Madison. “She said, ‘You need to read this book, because it could have been us.’ ’’ It was about the extermination camp at Treblinka, during World War II in Poland.

Dobbs asked her what she meant.

“Performing the Jewish Archives” is a $2.5 million grant to five universities to mount recently rediscovered Jewish musical, theatrical and literary works created from 1880 to 1950, and encourage the creation of new works based on archives.

Teri Dobbs. Photograph by Michael R. Anderson.

Her mom replied, “Well, your grandfather’s Jewish.” Dobbs was bewildered, and her mother explained: He was one of the only Jewish people in town, his mother having been part of a wave of Jewish immigrants in the late 19th century who became merchants, peddlers and farmers on the Great Plains. His name was Gerrit Dyke.

Dobbs kept reading. She asked questions. She wanted to know: How did a Dutch Jewish woman, Maria Louisa Rosenthal, land in the middle of South Dakota in the 1880s? After marrying Govert VanderBoom, a non-Jewish Dutch man, Maria Louisa took his name, but the name Rosenthal was not forgotten. Dobbs’ mom kept a trove of family papers, including Maria Louisa’s obituary, who in her papers consistently referred to herself as “Maria Louisa Rosenthal VanderBoom.” And, when asked, extended family members replied, “Yes, Maria was Jewish.” But that was the end of the conversation.

It wasn’t the end of Dobbs’ interest in Jewish history, however.

In 2002, she became a Jew by choice and married a Jewish man. As it happened, her husband, Jesse Markow, had a similar background: his grandfather, Morris (Moishe) Markov had emigrated from the Ukraine, from a shtetl called Markova, located in what was known then as the Pale of Jewish Settlement. Markow arrived in New York City around 1904 as a single man, with only a wooden flute in his pocket that he’d formerly played in the Russian czar’s army, and found his first job working at a laundry at the dockyards.

Dobbs’ husband, Jesse Markow, with his grandfather’s flute.

Neither Rosenthal nor Markov maintained any links to their former homelands. And so it was for so many expatriate Jews at that time.

Meanwhile, Dobbs grew up. She went to college at the University of South Dakota and served four years with the United States Air Force Academy Band as a flutist and singer, then taught band, orchestra, vocal music, and general music in Colorado, South Dakota, and Illinois. Later, in graduate school at Northwestern University, where she earned a master’s degree in 1992 and a Ph.D in music education in 2005, she found herself drawn to that Jewish history, and started delving into music created and performed during the Holocaust, or Shoah.

At UW-Madison, where she arrived in 2006 as an assistant (now associate) professor of music education, she focused on children’s musical experiences in the ghetto at Theresienstadt, known now as Terezín. During World War II, Terezín, an 18th-century fortified city in Czechoslovakia, not far from Prague, was converted by the Nazis into a transit camp for thousands of largely upper class, educated Jews, including well-known artists, writers, and composers, most of whom who ultimately were killed in concentration camps. One of those, the composer Hans Krasa, had written a children’s operetta, Brundibár, which was performed over 50 times by children at Terezín.

Artifacts from the children’s operetta, Brundibár.

Performing Brundibár provided a way for the Jews at Terezín to preserve some semblance of culture as society was disintegrating all around them. It also provided Dobbs the entrée into a field of study that had so long intrigued her.

In 2010, she began an intense study of the operetta, culminating in a paper published last fall in the Philosophy of Music Education Review, “Remembering the Singing of Silenced Voices: Brundibár and Problems of Pedagogy,” in which Dobbs explored the cognitive dissonance of music-making during wartime and questioned how the opera is taught today. On a recent sabbatical, she spent time researching the archives in the Jewish Museum of Prague and the Terezín Memorial, in addition to Yale University’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies and the Shoah Foundation Video History Archive at the University of Southern California.

In Prague, she interviewed survivors of Terezín, some of whom had sung in the Brundibár chorus. All shed light on how valuable the experience of music making was to people trapped inside the ghetto, and provide insight into music education today.

“Studying Brundibár is, in a way, studying the ‘present absence’ of people who are no longer with us,” Dobbs says. “When we hear the operetta, we hear the voices of children who were silenced.”

It turned out that Dobbs’ work fit perfectly within a framework being developed by researchers elsewhere.

Due to her pedagogical pedigree, Dobbs was recently named an international co-investigator in a $2.5 million grant to mount recently rediscovered Jewish musical, theatrical and literary works created from 1880 to 1950, and to encourage the creation of new works based on archives. The grant, called “Performing the Jewish Archive,” was awarded by the British Arts & Humanities Research Council, and is led by Dr. Stephen Muir at the University of Leeds in England. Other co-investigators include Dr. Helen Finch, School of Languages, Cultures and Societies, University of Leeds; Dr. Lisa Peschel, Film, Theatre and Television, University of York; Dr. Nick Barraclough, Psychology, University of York; Dr. Joseph Toltz, Sydney Conservatorium, University of Sydney; and Dr. David Fligg, Leeds College of Music.

The three-year “Performing the Jewish Archive” project will involve a large number of partners, exploring archives, delivering community and educational projects, holding at least two international conferences and a series of symposia at the British Library, as well as mounting five international performance festivals – in the United States, the Czech Republic, South Africa, Australia and Yorkshire, England. Madison — where two of those festivals will take place in 2015 and 2016 — is the only United States site to be chosen. The goal of the performance festivals is to uncover lost and damaged theater scripts, musical scores and works of literature so that they may be experienced by modern audiences.

Not so long ago, lead investigator Stephen Muir himself, on a trip to South Africa, unearthed a musical score called “One Little Goat” by a previously unknown Russian Jewish composer, David Eisenstadt (Dovid Ajzensztadt). Eisenstadt had lost his life at the Treblinka concentration camp but had given the manuscript to a friend to review. Decades ago, the score had wended its way to South Africa via a friend and was finally premiered last spring in England.

Brundibár is only one example of the wealth of Jewish performance art that has been lost for so long. And so the race is on to find others, to preserve them, and to present them. And for at least one researcher, it will also help open a door to her own past.

“Having the opportunity to do this kind of research/scholarship in many ways brings me full circle, connecting and reconnecting me with a part of my heritage that was hidden for so long,” says Dobbs. “It’s a way for me to return to my roots by remembering actively those who went before me, maybe even to make things a bit better for those who come after me. In Judaism, this can be considered a type of ‘tikkun olam,’ or ‘healing the world.'”

Read about Dobbs’ research in a story published in the online newsletter of the Center for Jewish Studies.

“Remembering the Singing of Silenced Voices”: Philosophy of Music Education Review, Fall 2013, Teryl Dobbs, author.

More media links:

It’s not very often that one receives international recognition 250 years after being placed in the ground. But with help from UW-Madison musicology professor Charles Dill and a host of international scholars and musicians, that’s exactly what’s happening for Jean-Philippe Rameau.

Rameau, a French composer (1683-1764) who lived during the reign of Louis XV, has become famous for his contributions to music theory, his early harpsichord works, and especially his operas. His 1722 Treatise on Harmony is considered revolutionary for having incorporated philosophical ideas alongside practical musical issues. His operas were equally famous for their rich choral singing and elegant dancing. In the last few decades, interest in Rameau has intensified, with French scholars leading the way and organizing major festivals in Europe. Because of Dill’s renown as a scholar of Rameau and the Baroque, the UW-Madison School of Music will present a series of performances and talks about Rameau during the 2014-2015 academic year.

On November 13, the first of these events will kick off with a discussion about the expressive qualities in Rameau’s music (with visiting opera director David Ronis and Professor Anne Vila of the Department of French and Italian), followed by a concert the next day featuring Marc Vallon, UW-Madison professor of bassoon, in a mostly-Rameau concert. You can read the full schedule of events here.

We asked Prof. Dill to tell us a bit about himself and what makes Rameau an important figure in music.

How did you first become interested in Rameau?

“Modern audiences often view all composers of the past as struggling visionaries. This may be true of composers after Beethoven, but it isn’t true—or isn’t true in the same way—for earlier composers, even composers like Mozart or Haydn. They considered themselves to be working at a job. They wrote pieces to suit their performers, and the compositions were ‘disposable.’ If something needed changing, the composer changed it, generally without much grumbling. They didn’t continue to garner attention for decades.

“What first interested me about Rameau, then, was that he revised his operas extensively and these revised versions continued to be performed. This suggests all sorts of remarkable things about him and his works. Notably, he was alert to how audiences responded to his works to an unusual degree, and he felt some kind of obligation toward ‘getting the work right,’ as it were. That’s a very modern way of thinking about music. Because of this attitude, he also took risks as a composer. He was a remarkably creative individual, and he was rewarded for it. His works dominated French opera for a period of fifty years, until well after his death. For his time and place, this truly was an unusual relationship between composer and audience.

“Add to that Rameau’s work as a theorist. Thinkers had been speculating about how music works for as long as music had existed, but Rameau was the first to envision a comprehensive system that accounted for all of its aspects: how keys or tonalities come into being, why some harmonic progressions are more effective than others, how musical knowledge influences performance. We still employ his basic terminology for describing fundamental principles of music—chord inversion, tonic, dominant. There were flaws in his ideas, to be sure, and there have been countless other systems proposed since that make similar claims, but if you imagine music as an organized, coherent system—something we do every day—then you are, to a degree, following in his footsteps.

“And finally, around the year 2000, everyone became much more interested in Rameau, in response to a series of extraordinarily good performances and recordings, many of them under the direction of William Christie. It is no exaggeration to say the world thinks of Rameau differently as a result of William Christie’s work with the group Les Arts Florissants.”

How did you become a Rameau specialist?

“I was fortunate to be in the right place at the right time. When I began working in Parisian libraries in the late 1980s, as a graduate student completing my degree, there were only a handful of people studying Rameau. Students from that generation have done influential work. Thomas Christensen explained the development of Rameau’s music theory, Sylvie Bouissou became the general editor of the Rameau edition, and William Christie specialized in interpreting Rameau’s music in performance.

“I was interested in Rameau’s relationship with audiences. Music criticism was still a fledgling enterprise in the eighteenth century, and yet his compositions elicited strong opinions, both for and against. He was one of the first composers to be treated not simply as a commodity, but as a public figure, one of the first to take that role seriously. To an unusual degree, he felt the need to experiment in his compositions, and yet he was also forced by circumstances to consider listeners and their perceptions in everything he wrote. After all this time, I still find this story remarkable.

“Times have changed. Nowadays, France recognizes Rameau as one its most representative composers and devotes time, money, and effort to developing our knowledge of him. A small army of dedicated French researchers is poring over every available source and producing first-rate scholarship. They’re doing wonderful work.”

What contributions have you made to scholarship?

“When I began writing about Rameau, there was a longstanding trend to approach composers solely from the vantage point of what they wrote. We could describe this as the ‘great composers’ or ‘great works’ approach. Discussing composers in this way cuts out some of the most interesting material: what audiences believed, how they liked what they heard, how they received the composers, and how composers responded to criticism. My book, Monstrous Opera: Rameau and the Tragic Tradition (1998), which Princeton University Press has recently reprinted as part of its Legacy series, addressed some of these questions. As an eminently public figure, Rameau was subject to intense scrutiny. Some critics distrusted opera as an overly sensual medium, and some regarded Rameau’s colorful music as an especially egregious example. Rameau encouraged these kinds of responses. Where earlier composers generally wrote simple, unobtrusive music, Rameau wrote music that demanded attention. In a way, then, he challenged critics and audience members to define their expectations regarding music openly and publicly. It is telling that, during the period in which he became popular, audiences changed, coming to resemble modern audiences more and more: they began to learn difficult and complex music by heart, they grew more quiet and became more attentive during performances.