From the Mead Witter School of Music

University of Wisconsin-Madison

September 13, 2016

In a marriage of the Baroque and the modern, celebrated UW-Madison pianist Christopher Taylor will debut his much-anticipated new electronic double-keyboard piano this October 28, performing J.S. Bach’s “Goldberg Variations.”

The “Variations” is an 80-minute work once dubbed a “Rubik’s Cube of invention and architecture” that Bach wrote around 1741 for a double-keyboard harpsichord.

Not by coincidence, Taylor will play Bach’s “Rubik’s cube” on a brand-new piano that could be described in much the same way.

Named the “Hyperpiano” by Taylor, it is actually three instruments – two of them ordinary concert grands, the third a special double-keyboard console designed by Taylor – connected by a riot of sensors and wires, with a mechanism that feels nearly normal for the performer but offers sonic possibilities that are unique.

Taylor developed the piano over several years in a laboratory at the Morgridge Institutes for Research, assisted by many faculty and technicians who trained him to machine new parts using computers and guided him as he designed 60-odd circuit boards that make the instrument run. In addition, Taylor wrote several thousand lines of computer code that manage sensing and communications. In 2014, Taylor received United States patent # 8,664,497 B2 for the “Hyperpiano.”

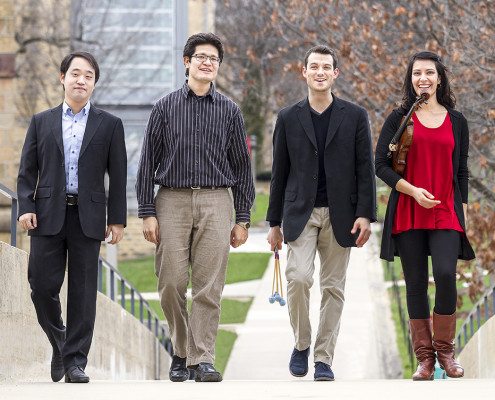

Taylor entering the “fab lab” at the Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery.

His inspiration to develop it came from another unusual instrument that he inherited shortly after coming to UW-Madison in 2000, a double-keyboard piano made by Steinway in 1929.

Johann Sebastian Bach was known as a composer who welcomed new concepts in musical instruments. Accordingly, Taylor says, Bach designed the Goldberg Variations for the most deluxe instrument of his day, a double-keyboard harpsichord with a four-and-a-half octave range. Today, musicians often perform the work on a regular piano, but must generally “resort to tricks, compromises, fudging or outright studio chicanery to play all the notes as Bach wrote them,” as writer Tom Huizenga wrote in his blog, “Deceptive Cadence.”

The Hyperpiano will allow Taylor to overcome those obstacles. “I can recreate effects more like what Bach imagined, even while producing at the same time completely novel musical results,” Taylor says.

Taylor was a bronze medal winner in the 1993 Van Cliburn International Piano Competition, at which he performed the Goldberg Variations, among other works, on a standard single-keyboard Steinway. He also holds a degree in mathematics from Harvard University.

The concert will take place on Friday, October 28, at 8 PM in Mills Hall, Humanities, 455 North Park Street. There will be one intermission.

Tickets for adults are $18; for students, $5. They may be purchased at Campus Arts Ticketing or in person at the Memorial Union Box Office.

Patrons are advised to arrive early.

Mills Hall seats 700, of which 100 seats will be reserved on a first-call basis for music students, staff and faculty.

Christopher Taylor’s “Hyperpiano” Creates New Musical Possibilities

By Michael Muckian

“I would never be content as a pianist to play the same half-dozen pieces the same way year in and year out,” Taylor explained. “In piano literature, we have a vast array of great compositions, but we are always questing for new variety.”

Christopher Taylor grew up in Boulder, Colorado, where his father taught physics at the University of Colorado and his mother was a high school English instructor. The family owned a piano and Taylor initially was taught to play by a neighbor down the street.

The casual lessons didn’t last long; by age 10, the young pianist was playing Beethoven. By high school he was composing music.

While music was his first love, Taylor also proved gifted in mathematics, a field that seemed to offer a more stable career path. The young pianist chose to follow that thread, graduating summa cum laude in mathematics from Harvard University in 1992.

During those same years, Taylor also studied piano under Russell Sherman at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where he began to attract the attention of the East Coast classical music community. In 1990, at the end of his sophomore year, Taylor won the University of Maryland’s William Kapell International Piano Competition, and later that same year made his performance debut in Alice Tully Hall at New York’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts.

However, Taylor’s watershed moment came in 1993 at the age of 23, when he earned a bronze medal at the quadrennial Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in Fort Worth, Texas, for his performances of works by Beethoven, Boulez and Brahms, as well as Bach’s “Goldberg Variations,” now a standard part of his repertoire. For the young mathematician-slash-pianist, the competition win sealed his fate.

Christopher Taylor performing in Mills Hall, Feb. 2015. Photo by Michael R. Anderson.

“I had sat on the fence between music and mathematics for many years, but the bronze medal made the decision for me,” Taylor said. But while his musical career had become ascendant, he kept up his math and computer studies. “I didn’t want to put the other parts of my brain on ice.”

The newly minted concert pianist, who would go on to earn critical accolades such as “frighteningly talented” (The New York Times) and “a great pianist” (The Los Angeles Times), knew that his mathematics training went far to inform and support his music.

Both disciplines draw on similar mental skill sets, Taylor explained, noting that hours of piano practice can provide the necessary rigor to solve a complex mathematical proof.

“Music performance is more visceral than math, but when I’m performing I am definitely using the logical part of my brain,” he added. “Mentally understanding a piece of music is essential to surviving a performance.”

Following the Van Cliburn competition win, Taylor became a touring musician. His new wife wanted to pursue her doctorate in musicology at the University of Michigan, so the couple moved to Ann Arbor while Taylor spent weeks on the road playing several dozen concerts per year across the U.S. and in Europe.

Life on the road proved strenuous for the young pianist, who became known for his intense, sweat-soaked, highly physical performances. Eventually, Taylor decided he might want to teach. When the University of Wisconsin offered Taylor a faculty position in 2000, his family moved to Madison.

At UW-Madison, Taylor came across a prototype that would prove the foundation for his new invention. And he can credit a little known Hungarian composer for the introduction.

Emánuel Moór, who during his life composed five operas, eight symphonies and other orchestral works, is best remembered today as the inventor of the Moór Pianoforte, a double-keyboard instrument that attempted to replicate the benefits of the harpsichord and organ in the piano format. It boasted a two-tiered keyboard, but space within the cabinet allowed for only 76 keys on the top tier instead of the usual 88. The layout of the 164 keys allowed one hand to stretch across a range of over two octaves at once, creating a richer and fuller sound.

Watch a video of Taylor describing his plan for a new piano.

Moór was a professional colleague of composer Maurice Ravel and cellist Pablo Casals, both of whom championed his work, including his pianoforte. Despite such celebrity support, many musicians considered Moór’s instrument more of a novelty and found it difficult, if not impossible, to play.

European manufacturers produced about 60 pianofortes during the 1920s, including one made in 1929 in Hamburg, Germany, by Steinway. Until very recently, that particular instrument occupied a corner of Taylor’s cramped office in the Mosse Humanities Building.

The Moór pianoforte found its way to UW-Madison after Danish pianist Gunnar Johansen became the university’s artist in residence in 1939. Enthralled with the strange instrument, Johansen lobbied university donors until they broke down and bought it for him on the condition that its ownership revert to the university upon the pianist’s death.

By the time Johansen died in 1991, interest in the pianoforte had waned. It lay in storage for 14 years until Taylor rediscovered it in 2005. He performed on the pianoforte in dozens of concerts across the country, eventually getting a feel for the instrument and gaining notoriety for his performances. In 2007, the New York Times interviewed Taylor and created a video about the piano. In 2010, while he was in Washington, D.C. for a performance, the Kennedy Center created its own version.

“It’s clever as a musical contrivance, but it’s a little unwieldy and feels strange under your fingers,” Taylor said, noting that corresponding keys on both keyboards end up striking the same string. “You have to work very hard to play the keys because of the Rube Goldberg mechanism that connects them with the hammers.”

Around 2009, having studied the levers, rods, and platforms lurking inside the Moór piano, Taylor decided there might be a better way, a way that would take advantage of 21st-century technology. He began to draw up blueprints, discussed his ideas with a number of experts, and eventually received a grant from the UW Arts Institute to pursue them further. In early 2012 he approached George Petry, a prototyping manager at the Morgridge Institute for Research, to talk about his idea, an idea that much later would be named the “Hyperpiano.” Petry thought Taylor was nuts.

“I thought Chris was crazy because I knew this was going to be so much work,” Petry said. “I have a lot of students coming in who have never built anything before who say they want to build a space shuttle. I thought this was Chris’s space shuttle.”

But Petry gave Taylor the benefit of the doubt, and also a corner in the Morgridge Institute’s Advanced Fabrication Laboratory – better known as the “fab lab” — inside the Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery building on University Avenue, a home where engineers and inventors collaborate to build prototypes of their ideas. And Petry started to teach Taylor how to use all the computer-operated machines.

Another important teacher was Giri Venkataramanan, a professor in the UW-Madison Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering who served as a high-level consultant to the project. “His motivation was sky-high and it sounded like he knew what he was doing,” Venkataramanan said.

At first blush, the Hyperpiano’s double-keyboard console – what Taylor calls the “input device” – looks like a contemporary upright piano that is thicker in girth than normal. It features a two-tiered keyboard with 176 keys total along with five pedals. Hidden inside the cabinet, behind the keys, are two sets of standard mass-produced piano hammers.

But that is where similarities to a regular piano end. There are no strings for these hammers to strike, and Taylor admits that their only function is to mimic the feel of playing a normal single-keyboard piano. In fact, in the absence of strings Taylor had to create special foam bars for the hammers to strike, designed to replicate an ordinary instrument’s behavior but create as little “banging” noise as possible.

“Even building a conventional piano that works is a very difficult process in itself,” says Robert Hohf, a professional piano technician who aided Taylor. “The keyboard orientation and the alignment of parts is unbelievably complicated.”

And with the Hyperpiano, the complications only increased.

Designing an instrument that contains twice the normal number of keys and twice as many hammers, aligning everything inside a single wooden frame, took a massive amount of re-engineering, Taylor says. Each of the 176 keys in the Hyperpiano has a unique shape that had to be specially carved by a router, which got its directions from multiple computer programs written by Taylor.

To actually make music, the double-keyboard console contains electronic sensors that read the movement of the keys during each stroke, then send coded electronic impulses via wires to two player-piano mechanisms called “Vorsetzers.” (First developed in the early twentieth century, Vorsetzers were mechanical key-pressing contraptions that could be attached to the keyboards of ordinary pianos.) The Vorsetzers are affixed to any pair of pianos one has handy, which, in theory, could be some distance away. Thus the motions of the pianist’s fingers on one part of the stage are transmitted instantaneously to produce music emanating from two other parts of the stage.

Taylor plays Prokofiev

Timing everything so that the music would sound like music—not a jangle of disparate noises – was another hurdle Taylor had to surmount. Taylor’s new technology solves that problem: it senses a fraction of a millimeter of motion as soon as a key is pressed. The sensors immediately send the data to the Vorsetzers, which move the corresponding key the same amount at exactly the same time.

“It involved a lot of software jujitsu to make this happen,” he said. But in the end, “everything is choreographed to deliver the final notes in real time,” he explained.

The Hyperpiano could afford some novel performance opportunities, says Taylor: “For starters, it will be capable of everything the Moór piano can produce: far-flung chords beyond the grasp of ordinary human hands on ordinary pianos, intricate counterpoint where the hands mingle in the same register (effects that would cause impossible traffic jams on a single keyboard), and, with the aid of an extra fourth pedal, sonorities reinforced by extra tones one octave higher than the keys the pianist is actually pressing.

“But it will offer customized behaviors beyond these,” he continues. “The ability to reinforce the pianist’s keypresses with any number of additional notes, so that the motion of a single finger produces an elaborate harmony; novel hybrid sonorities obtained by combining different pedaling patterns on the two subsidiary pianos; repeated notes faster than what ordinary pianos permit; and the interesting spatial effects that will result when the two subsidiary pianos get rolled to different parts of the stage.”

Taylor is eager to produce new arrangements and compositions that take advantage of these musical novelties. “I’m in discussions with a number of composers about the possibility of their contributing to a new chapter in the piano literature,” he says.

With the end of the project in sight, the pianist says he’s pleased with the outcome of his years of work, even as he adjusts to new variations in sound and performance.

“I’m delighted to find that the final product is matching my initial vision pretty closely,” Taylor says. “There is still some tweaking that needs to take place — software refinements mostly — in order to ensure that as a pianist I have the level of musical control that I need. This work may prove challenging, but as in the past I am very determined to overcome the remaining obstacles.”

Venkataramanan agrees and also is thinking ahead to the piano’s next iteration.

Scientists, unfortunately, are never satisfied.

“As a problem-solving exercise, this has been pretty impressive,” the engineering professor says. “But he still runs wires between his keyboards. The next phase would be to do this on a wireless basis and using Cloud technology.”

Mr. Taylor is eager to acknowledge the invaluable help he received from a large number of collaborators over the past five years. Apart from piano technician Robert Hohf, machinist George Petry, and EE Professor Giri Venkataramanan, these individuals include: Rock Mackie and Kevin Eliceiri, the former and current directors of the Morgridge Institute for Research, who were amazingly welcoming hosts during his four-plus years in the Fab Lab; UW-Madison piano technician Baoli Liu; Justin Anderson at WARF and Callie Bell of Bell Manning LLC, who shepherded the patent application process; Kevin Earley, who built the wooden housing for the input console; Convenience Electronics of Madison (in particular Betsy Vanden Wymelenberg), who custom assembled the instrument’s many wires and cables; Calvin Cherry, Nate Hess, Brian Urso, and Ryan Solberg, whom Taylor employed to solder together circuit boards and who contributed greatly to his EE education; UW-Madison’s Bill Sethares, along with Terence O’Laughlin and Alberto Rodriguez of Madison College, who put Taylor in contact with the aforementioned companies and employees; and the UW Arts Institute, former chancellor John Wiley, and Paul Collins, who provided moral as well as financial support.